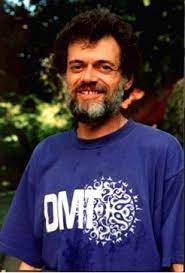

“Bard of the Archaic Revival”

Terence McKenna, the visionary ethnobotanist and self-proclaimed “bard of the archaic revival,” offered a unique, often exhilarating, and occasionally alarming perspective on the burgeoning cyberculture of the late 20th century. Far from a conventional technologist, McKenna approached the digital realm through the lens of psychedelics, shamanism, and a deep, almost mystical, understanding of information. For him, cyberculture was not merely a technological advancement but a fundamental transformation of human consciousness, echoing the hyper-connectedness of mycelial networks and potentially culminating in a “telepathic hyperspatial continuum” that transcended physical reality. His analysis, often delivered in captivating, improvisational lectures, served as both a celebration of digital potential and a cautionary tale of its profound implications.

McKenna’s central argument concerning cyberculture hinged on the idea that technology, particularly digital technology, was the “real skin of our species.” He saw humanity as an “extruder of technological material,” constantly pushing the boundaries of what is possible, from simple tools to complex machines. Cyberculture, with its emphasis on virtual reality and global interconnectedness, represented a pinnacle of this extrusion, a “technological reef of extruded psychic objects” that would ultimately become a mirror of the human soul. For McKenna, the internet and virtual reality were not just communication tools; they were embryonic forms of a collective consciousness, a digital “Logos” that would allow humanity to externalize its inner world and share it in unprecedented ways.

One of the most compelling aspects of McKenna’s cyberculture analysis was his fervent belief that virtual reality (VR) offered a path toward a “telepathic hyperspatial continuum.” He envisioned VR as a means to “objectify language,” allowing individuals to “see what we meant when we spoke.” This, he argued, would overcome the inherent limitations of spoken and written language, which he viewed as crude “small mouth noises” or “scribbled squiggles.” In a VR environment, meaning itself could become tangible, visually rendered in three-dimensional space, thereby leading to a form of telepathy where ambiguity and misunderstanding would dissolve. This vision aligned with his psychedelic experiences, where he often encountered “machine elves” or “the Logos” – entities that communicated in a visually rich, non-linguistic manner, suggesting a form of communication beyond human comprehension. For McKenna, VR was the technological analogue to the psychedelic experience, a means to access and share these higher states of consciousness.

However, McKenna’s enthusiasm for cyberculture was tempered by a profound understanding of its potential dangers. He frequently warned against the pitfalls of technology that becomes an end in itself, divorced from the human spirit. He recognized the risk of “selling the technology before anybody really knew what its purpose should be,” a prescient observation given the rapid, often unreflective, proliferation of digital tools. McKenna was particularly wary of technology that contributed to a sense of alienation or served to reinforce the “dominator culture” he so frequently critiqued. He saw the potential for cyberculture to become another mechanism of control, diverting humanity from its true purpose of “deconditioning ourselves from 10,000 years of bad behavior” and re-establishing a harmonious relationship with nature.

Indeed, McKenna often contrasted the promise of cyberculture with the importance of the natural world. While he believed in an “ultra-technology in a dimension that is split-off from what is called ‘the ordinary world’,” he also advocated for maintaining the “natural world” as a “botanical garden or a natural preserve.” This duality highlighted his concern that an overemphasis on the virtual could lead to a further disconnection from the ecological roots of human experience. He believed that the ultimate “fantasy” for technology was not to escape nature but to create a “mirror of our own souls” that would allow us to better understand and integrate with the natural world, rather than simply fleeing it.

Ultimately, Terence McKenna’s take on cyberculture was deeply intertwined with his broader philosophical project: the “archaic revival.” He saw the digital revolution as a potential catalyst for humanity to reconnect with its shamanic roots, to embrace altered states of consciousness, and to move beyond the limitations of reductionist materialism. For him, cyberculture was not just about faster communication or more immersive entertainment; it was about the collective re-imagining of reality itself. While his prophecies of a fully telepathic, hyperspatial VR haven’t materialized in the way he envisioned, his insights into the transformative power of interconnectedness, the potential for digital alienation, and the profound link between technology and consciousness remain remarkably relevant in an increasingly cybernetic world. He challenges us to consider not just what we build with technology, but why, and whether our creations are truly serving the evolution of consciousness or merely perpetuating old patterns of control and illusion.

LITERATURE:

The Invisible Landscape: Mind, Hallucinogens & the I Ching

Terence McKenna, Dennis J. McKenna

A thoroughly revised edition of the much-sought-after early work by Terence and Dennis McKenna that looks at shamanism, altered states of consciousness, and the organic unity of the King Wen sequence of the I Ching.

Links

https://citizenmediaseries.org/2014/12/17/introducing-cyberculture

Discover more from Virtual Identity

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.