Tony Gregory intercultual psychologist

In 1962, Thomas Kuhn published the most important intellectual work of the 20th century, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In it he argued against the long-held belief that evolution was an uninterrupted and steady continuum. He posited instead that progress came in jerks and starts – long periods of calm that were managed according to widely accepted beliefs and customs interspersed with brief violent periods of enormous change, like the renaissance, when all that had been accepted before was challenged and frequently overthrown. He called these violent brief periods 'paradigm shifts,' and since that time it has become an accepted part of how we see our world.

It was not long after that that Alvin Toffler wrote Future Shock, in which he argued that not only was Kuhn correct, but that the periods of relative stability between the brief and violent episodes of change were becoming shorter, so short in fact that it challenged out ability as humans to adjust to one set of revolutionary changes before another set was already upon us.

He gave as an example the impact of railroads on history. When Julius Caesar marched his legions south from France to Italy to conquer Rome in the first century AD it took more or less the same time as it took Napoleon to cover the same distance seventeen hundred years later. But it was only forty years after that when the railroad linking France and Italy was completed, cutting the journey from two months to three days. When Lincoln was assassinated in 865, it was only noon the next day that they heard about it in San Francisco. I saw the assassination of Robert Kennedy live – at the same time it happened – a century later. There are many examples you can give, but the impact is similar – changes coming at such a fast pace produce stress, and stress is the handmaiden of paradigm change.

One of the most important insights about paradigm shifts is that the animals that did well following the rules of the previous paradigm did not do well in the new one if they continued to follow those same rules because all the rules had changed (just ask the dinosaurs). People that owned stables during the age of agriculture were no longer at the center of things when the automobile replaced the horse as the accepted means of transportation. Quite clearly, there is a clear message here – if the paradigm changes and you don't, your future looks bleak.

But it is important to point out that not all paradigm changes are the same. The industrial revolution was a definite change in paradigms, and economic power in the world shifted dramatically from an emphasis on ownership of land to an emphasis on access to raw materials and the means of production. Yet the family structure survived the change, as did religion and nationalism.

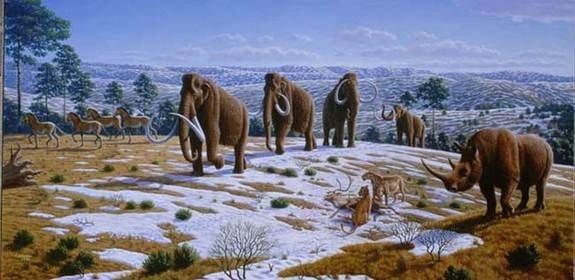

The change from the ice age to the Holocene period which we presently inhabit was also a paradigm shift, but one far more powerful than the movement from agriculture to industry. When the glaciers finally retreated and the planet warmed, our species (Homo sapiens in case you forgot) spread around the globe and our numbers exploded because it became possible for us to sustain ourselves in far larger groups, which in turn allowed us to do things we had never done before, like build permanent dwellings and use the land to provide us with food on a continual basis, which we called agriculture.

We actually started recording events then, some ten thousand years ago – we call it history. The concentration of our species in such large numbers created a need to order things, to solve disputes and regulate affairs, and that led to the birth of customs, religion and culture and the domestication of animals. I could go on but I think you get the point – the change was so dramatic that nothing that had been true before remained. It was a transformation.

The other thing to point out is that all of this happened slowly, over the period of more than one lifetime. The people that came south after the glaciers retreated were long gone before the first cities were built and the first empires were formed. Akkadia was the first human empire, formed in Mesopotamia 4300 years ago, and that’s a full five thousand years after the glaciers began to retreat. We had time to adjust, time to consider how to respond to our new reality, time to try different ways of approaching things, and time to fail and try something else and still survive (unlike the Neanderthals).

Now, at the beginning of what we call our twenty-first century since we started writing stuff down, it appears that we are on the verge of a new paradigm shift, and possibly one as dramatic as that last big one when the ice retreated. If that is true, then we should remember that insight from so long ago – nothing that went before remained. That is the mark of a complete transformation.

It's tough for us to think about that because whether we like it or not we are children of our current paradigm, formed by its assumptions, educated in its customs and brainwashed accordingly. We find it difficult to think of ourselves without these things we are wedded to. Look, when Copernicus stepped forward in 1543 and said "Uh…I just want to point out that the earth is not the center , it’s the sun" even very smart people had a hard time wrapping their heads around that. It took literally a hundred years before it was accepted as a scientific proof (except in parts of the United States where science is still not accepted until this day). That is called denial of reality, and back then a lot of people were in that state for an extended period of time.

So when I step up and suggest that everything is about to change, not just the small stuff, I imagine that a lot of people – smart people – will find that hard to accept. Nevertheless, I think our ice age is about to end, and, in the spirit of Alvin Toffler, I think the new paradigm will be upon us so quickly that we will not have a lot of time to react. So, with that proviso, here is my preview of the next paradigm. Please forgive me if not all of the changes are of the same magnitude and if I leave some out. I, too, am a child of our current paradigm, and like everyone else my vision to see ahead is both limited and subjective.

We have become accustomed to identifying ourselves in relation to other people, to our geographical location, our membership in some political group ( a nation) and to our occupation, and to what we believe, which the more extreme among us label 'the truth.' So, I say I am a father, a husband, a member of a certain family, a citizen of a community and a nation, and I work as a psychologist - and all of that is about to change.

WORK

let's start with the easy one – work. There is not enough of it to go around. In our current paradigm we regard unemployment as some sort of negative state, a disease that needs to be treated. We talk about work moving around the world and call it outsourcing. We act as if the lack of jobs in North America means those same jobs have somehow magically moved to Asia and it is the cause of a great deal of unrest. None of that is true.

What is true is that human work, as we have come to know it during the last three centuries, is disappearing. What was once done by human labor is now done by machines. In a report on Automation in 2020, the World Economic Forum predicted by the year 2025, 53% of work would be performed by humans and 47% by machines, a 14% increase from the year the report was issued. If you carry that ratio forward then all work will be done by machines before the year 2060. But forget the numbers game. The impact of automation is that work will cease to be the center of life as it has been during the last three centuries.

It's not only that people will not physically move to find work, like they moved from the country to the cities at the start of the industrial revolution. It means there will be no place to move to. The family will not have to sacrifice some part of their life so that the wage earner can do his job, there simply will be no wage earner. People's income from work will not have to be supplemented by government spending when it is not enough because there will be no income from work. That is the nature of a complete transformation.

Income will not be apportioned on the basis of achievement (higher salary for work that is valued more highly) but existentially– you will not get money because of what you do but rather because of who you are. Iran was the first country to install universal basic income in 2010, and the practice is now prevalent throughout northern Europe. In an economic sense it is inevitable. If people depend on work for income, when there is no work, people starve, and when people starve, they revolt and topple governments (Just ask Louis the XVI). Every government on earth will take steps to prevent that.

Once work is no longer a benchmark of identification, the status distributed on the basis of occupation or position will cease to exist. A manager will not be more important than a laborer; a doctor will not have higher status than a janitor because these jobs will cease to exist. The subtle but unmistakable prejudice of assigning credibility based on occupation (doctors must be smarter than gardeners) will slowly fade away and people will be judged on who they really are rather than the work they perform.

Organizations will look completely different, and all the silly talk about organizational 'culture' will cease (thank God) because machines aren't in need of culture. The center of life will not be the place of work, there will be no traffic jams nor daily disruption of activities because of the physical need to move from one place to another, and identity will have to emanate from something other than where you work, because there will be no such thing.

Some things will remain. There will probably be teachers to some extent, though most instruction will be provided by machines, and there will be caretakers for more intimate human contact, though again, basic medical functions will be fully automated. Entertainment may remain a human occupation in some form, though it is important to point out that today most of the most popular entertainment is now animation (80% of top box office receipts in 2019 came from Disney studios and the most popular films tend to feature cartoon characters rather than human beings).

The clincher in all of this is time. We had eons to adjust from a nomadic life style to living in permanent communities. We will have just decades to adjust from a world with work to a world without work and it will leave literally billions of people gasping to find something to do. Some people like to compare what will happen to that old experiment of putting the frog in a pot of lukewarm water and heating it slowly so the frog doesn’t notice until he's cooked, but that isn't what will happen. The changes will be so fast that we will feel ourselves cooking, and it won't be pleasant.

FAMILY

Family has been the anchor of our identity for longer than work, probably for the last fifteen to twenty thousand years. It is without doubt the most emotionally-charged part of our identity, and most of our great works of literature deal with it from Oedipus to Anna Karenina. There is a natural inclination for a species to nurture its young; this is not exclusive to mammals. What is exclusive is the tendency of mammals to remain in units defined by a common blood line for an extended period of time, and among the mammals we humans are the champs. We extend our families for generations and we have made them the center of our lives, once again, for good and ill.

Part of the reason for this is survival. In the beginning if you were sick or injured you would not survive unless there were other people around you who cared enough to tend to you. More recently, the bond of survival has not been exclusively physical but also economic. Especially in the current generation, children in the west in particular are less well-off financially than their parents and without that support they would not make it. Like the man said, family is the place that when you go there they have to take you in.

There is an attendant pride that accompanies family identity, particularly when the family is adept either at maintaining a certain status (aristocracy, for example) or occupation (the military, for example). So, there are families of hostlers, shoemakers, haberdashers, iron-workers, doctors, and so on, and the connection between familial and occupational identity makes these families stronger over time. They exert pressure on their young to 'follow in their footsteps' and to adopt their ideals and beliefs, and believe this continuity has great value.

The industrial revolution weakened this bond for all but the wealthiest, causing as it did displacement of millions of people who found it necessary to move away from their place of origin to another community in order to secure employment, and the division of labor into employers and employees weakened the family ties of the latter and in millions of cases made it impossible for them to maintain the occupation or trade of the previous generations. The evolution of humanity from family-based to community-based dates from this time, about three hundred years ago.

But the real dismemberment of the family has been prosperity. As people become wealthier, on the top of their agenda is the desire to distance themselves from others. This has now arrived at a situation in which one out of every seven households in the United States is listed as a single person residence, and the situation in many major European cities is even more pronounced. In popular culture the familial bond has been replaced by the comradely bond, i.e. people you meet are closer to you than people of your same blood. In turn, this has led to a decrease in marriages and birthrates, and it becomes a self-propagating loop.

The coming identity paradigm holds a future in which the individual will replace the family as the basic social unit. Clearly, this is such a revolution that it is difficult for most people to imagine, but it is on the way, supported by the development of virtual relationships as a replacement for close physical relationships, meaning the sensation of being close to a person without ever being in the same room with him or her.

This is already well underway, egged on by social media, which encourages the individual to remain isolated from others in a physical sense in preference of a virtual connection. It is a common sight now to see a group of people 'together' in a public place not speaking to each other but rather managing a dialogue with a cell phone with somebody else who is not in the room.

Unlike the loss of work, which is a phenomenon not dictated or controlled by personal choice, this movement toward the individual in place of the family unit will take time, tempered by economic factors as well as strong cultural opposition, but it is coming nonetheless and will be the norm for most places on the planet by the end of the century. There are already sections of big cities like Tokyo that are intended for the exclusive use of young people, as well as adult communities restricted to those over the age of 65.

Multi-generational living arrangements are already largely a thing of the past globally, particularly beyond the nuclear family. The cultural consequences of this change are immense and frankly frightening for me to contemplate. Practically, it means that we will need to find new ways to transfer property and assign responsibility (designated driver will replace parent). Emotionally, we will go through a hard time when we dismember old axioms like 'blood is thicker than water,' because quite clearly, with all of its attraction, collegial ties will never take on the commitment that blood ties have. In the new identity paradigm, the family will disappear.

BELONGING

Belonging is such a central pillar of our current paradigm that it has been enshrined as a key component of mental health. People who shun contact with others are not just considered anti-social; they are labeled as mentally unwell (autistic). Mass movements were a central feature of the last two centuries, both political and social. Whether they were as benign as scouting organizations or as controversial as political protests, being part of some action which involved thousands of other people gathering together was a mainstay of life in every country on the planet. This is now coming to an end.

People will still voice their opinions, but they will do so online. Even dating has become a virtual activity rather than a night out; you check out a person's profile in the privacy of your own home long before you meet them. The same is true of voting and all forms of political activity. Not only can it be done from the home, it is being done from the home. The key to watch here is sporting events, one of the more acceptable reasons to mix physically with thousands of other people. When people begin to prefer viewing the events on a screen rather than sitting in a stadium, public participation will be terminated because it will become unprofitable.

Again, there will still be instances where thousands if not millions of people will express their opinions on a common topic, but this will be done in real time, surveys conducted by pressing a button on your phone rather than driving to a common location.

The mental health community will be forced to redesign conclusions about what it means to be alone. Indeed, loneliness itself will need to be redefined. Are you really alone (not lonely) if you are physically removed from everyone else but your cell phone is by your side? There will be a whole new list of mental conditions when the common living situation is one person alone. Clearly, there will be fewer problems resulting from interpersonal conflict (like domestic violence) because there will be fewer people living together. On the other hand, a whole new list of ailments will pop up because there will not be that other person in the room that can tell you when you are wrong. It will be a new world.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Our present paradigm has been flavored with our conceit that we are masters of the world, that we could bend the natural laws to our will, that we had some sort of irresistible control over everything. I suppose that the climate crisis is enough evidence to demonstrate what a mistake that was, but there is something even closer to home that will shake us to our roots in the new paradigm – we are no longer calling the shots.

Artificial intelligence will be the driving force in the new paradigm, and algorithms will make decisions in a distinctly different way than human beings. The lead elements of this new force are already changing the buying and selling of stocks and bonds and the application of medical procedures in hospitals all over the world. In the space of a few decades, all transportation will be directed by artificial intelligence, and drones and driver-less vehicles will be the norm (There will be no more human drivers or pilots because they are too dangerous). Manufacturing is already there, but there will be complete automation by the middle of the century.

AI will take the lead in education and customer service and the last pathetic attempts to suggest that the room for human work is just moving to other occupations will fall mute. In the new paradigm we will cease to make decisions about anything other than what we want personally, and that too will be limited. This is the one that scares me the most, but unless I take advantage of the next big change I won't be around, so it won't matter.

Human beings are used to making decisions. For a long time our ability to do this well was intimately tied to our survival. The idea that this will be taken from us because AI will do it better is a conclusion that many of us will find hard to swallow, and we will be reaching for that phantom limb long after it has been removed. Old people who believe they can drive just as well at the age of eighty as they did when they were 20 is a hint of what it will feel like. When the reality sets in that this is not rue it will likely be accompanied by a depression that will be very difficult to deal with, maybe even tied to the meaning of life. It will be a global emotional crisis that more than likely will trigger new forms of belief.

MORTALITY

Yuval Harari has been writing for some time about the conquest of death. At the present time, eight vital organs can be transplanted: the heart, kidneys, liver, lungs, pancreas, intestine, thymus and uterus. Artificial limbs are now commonplace, as well as eye transplants, artificial bladder implants, inner ear implants, and deep brain stimulation. The practicality of replacing the entire body, other than some higher functions of the brain, is now a distinct possibility before the middle of the century.

That means that your body no longer defines who you are, nor are you limited to a specific number of years before you 'die.' 'Life' will have to be redefined when it is not followed by the modifier 'time.' Immortality is a daunting moral and philosophical challenge, but it is no longer a physical one. It is very likely that the possibility of living longer will have a dramatic effect on birthrates, as the idea of passing the torch to a new generation, what Richard Dawkins called The Selfish Gene, will become a remnant of thinking from the previous paradigm, because that thinking is based on the assumption that the existing organism cannot sustain itself beyond a certain date.

No doubt the conquest of mortality will also lead to significant changes in relationships that were previous thought of (at least in theory) as life time commitments, like marriage and even parenthood. It will also be marked by the development of a whole new industry dedicated to the total replacement of the body, possibly with gender changes thrown in for a little spice – live eighty years as a man and another eighty years as a woman.

Immortality combined with artificial intelligence will demand an entire rethinking of the role of Homo sapiens on the planet, as well as how we define spirituality (if all of us are immortal how does this change the status of deities?). It is a daunting prospect. Things that we regarded as one-time decisions will lose that distinction, and almost everything will become choice-determined. Death itself will become a decision, not inevitability, and this alone will completely reshape philosophy and morality.

NATIONALITY

For the past several centuries we have defined ourselves as members of one nationality or another to such an extent that human beings were willing to die to protect or extend that abstract concept, something that commanded our loyalty even more than family or religion.

Most of us tend to forget our previous participation in smaller political units like tribes and regions, and for the most part these remain as romantic abstractions, lacking the full force of what it means to be a system of a country. Those pictures of Uncle Sam pointing his finger at you and calling you to enlist are not just propaganda, they are the expression of the belief of the country that it has the right to demand that its citizens give their lives to protect it. In the country in which I live this is a reality, and the state is by law authorized to exert its domain over the private lives of its citizens.

Because of the maximum commitment it involves, most of us are highly emotional about what we call our national identity. Yet nations, too, may not be a part of the next paradigm, as difficult as it is to believe. There is a contractual need for people to align themselves with a large political entity that manages an infrastructure. We need water, electricity, transportation systems and supply chains, and these are arrangements beyond the power or resources of any individual. But they are definitely contractual, and by no mean the exclusive rights or ability of nations.

In practice – not theory, practice – power companies in the United States can supply energy to all the homes of North America and maybe South America as well. The practice of ending the power grid at a country's borders is a political decision, not a technological one.

There is also no practical reason why a person living in Caracas cannot contract with a company half way around the globe, say India, for the supply of needed services, if that supplier is capable of meeting the demand. When it becomes clear that the supply of services that were formally relegated only to nations – security, welfare, transportation, health, energy, waste disposal, and more – can be supplied to individuals by a more effective alternative, then the grip of nations on individuals will slip.

The people of Catalonia do not want to be part of Spain, and the people of California have their doubts about the United States, yet this dissatisfaction with the larger national unity is still just a little step, the dismantling of larger political bodies into smaller ones.

There is a real possibility that the next paradigm holds a much more dramatic change in store – the alliance of the individual with an organizing structure beyond nations. Instead of a process of unification that produces ever bigger political bodies, think of it in the other direction – the existence of thousands of service providers making direct contact with consumers directly on a non-geographical basis, and not using a government as an agent.

So, for example, the person living in London might receive his mail from a supplier in Delhi, his power from a supplier in Norway, his security from a company in Scotland, and his health from an organization in Switzerland. He may still consider himself English, but this will have more to do with his physical surroundings than with the political structure associated with it.

Quite clearly such a dramatic change has immeasurable implications for property ownership and civil legislation of every kind, and the number of lawyers required to work it out I don't even want to think about, but the point is that on a practical level it is indeed possible. It is only the abstract concept of nations for which so many people laid down their lives in the previous century that keeps it from happening. Nations have traditionally promoted themselves by their opposition to other nations, a practice which was expensive and bloody (we are better than they are; they want to kill us, so let's kill them first). If there is a business model that proves to be much more cost-efficient than the national one (and less bloody), it will come to pass, and within the next one hundred years, though I know how hard that is to believe. Yes, nations may be a thing of the past.

There will be a lot of gnashing of teeth when contemplating the alternatives, and there will remain a true need for the collection of public money in order to finance projects for the good of all (taxes), and there will always be disagreements over decisions made and the need to handle the losers so that they do not act to disrupt the system – all of that is true, but there is no natural law that says this must be the work of nations. The fact is that many nations are artificial in the extreme, the deformed children of colonialism, places like Pakistan and India and many states in Africa. The attempt to supplant such constructions with something else more effective is a positive idea, and it will be pursued.

RELIGION

The final pillar of identity that will be challenged in the new paradigm is belief. For the last millennium, many individuals have defined who they are as members of some religious movement, with Christianity and Islam being the most prominent recent examples. More blood has been spilled trying to sway different parts of the world to one religion or another over the last millennium than any other cause. This was challenged a half millennium ago when Christianity finally started to come apart into disparate elements of Protestantism and Catholicism and has been echoed more recently with the division of Islam into Sunni and Shiite. Still, many nations are defined by their religion. There are more than 80 nations today that officially give preference to one religion over another, including the one in which I reside.

Yet that, too, will be challenged by the impact of the new identity paradigm. In 2020, church membership in the United States dropped below 50% for the first time since the Gallup Poll began reporting. The American Mosque Survey reported a similar decline in the number of African Americans attending mosques in the United States. Similar situations are found in Europe. The Muslim population in Asia is still growing, but at a slower rate than was true half a century ago. Christianity in Latin America is becoming increasing more Pentecostal and less Catholic.

This does not mean that in the new paradigm religion will not play a role, but it does seem to indicate that the role will be much more individualized and much less public. In other words, the practice of mass movements of people professing the same belief who attempt to forcibly take over various parts of the world to install that belief seems to be coming at an end. It will take some time to realize that, but certainly most everyone can see that religious leaders today of whatever ilk are less influential in their ability to sway global events than they were even a hundred years ago.

Nations like Iran may still claim some sort of religious intent in their dealings with other nations, but this will become much less convincing during the next few decades, and most people will see it for what it really is – a political movement masquerading as a belief. A recent survey conducted in Iran suggested that about 40% of the country identified itself as actively Muslim in opposition to the official state claim of 99%.

***

Imagine for a moment a human being who is not defined by his nationality, place in a family, age, and membership in a religion, race, occupation, status or gender. How, then, is he to be defined? - Purely by his or her actions, emotions and thoughts, and what he or she makes from them? It would be true individuality, an identity that would make grouping impossible and therefore defy prejudice or assumptions. You would need to assess each person you meet in depth to really get to know them, because there would be no basis on which to make assumptions.

Patterns of course would eventually develop, they always do, but the base for these patterns would be different. We will no longer here things like "all women are…" or "Blacks are always…" or "Jews all are…" because there will be no meaning to these old distinctions. It would be like saying all Huguenots are the same or all Wares are the same, because these groups no longer exist. Some people will think alike, have the same taste, wear similar fashions, believe similar things, but those like-minded people will come from a wide variety of what used to be called mutually exclusive groups in the old paradigm, our paradigm.

I know that these observations may make some people uncomfortable; I know they make me uncomfortable. We are creatures of our times, and many of us have gotten ahead by following closely the rules that our paradigm gave us. So why is it that we need a new paradigm when so many of us are comfortable with the one we have even with all of its flaws?

Well, I don't think anyone did a survey of the woolly mammoths before the end of the ice age. It turned out that the paradigm shift was beyond their control, and their extinction was one of the unfortunate consequences of it. The truth is that many of the decisions we made over the last few centuries have consequences that we did not intend nor want, but they are consequences nonetheless. Who could have predicted that prosperity would lead to a desire to separate and not to join? Yet this is where the evolution of our species has led us – to a complete redefinition of who we are. We are subject to the consequences of our own actions, intentional or not.

I suppose in the middle of the feudal millennium many smart people would have found it hard to believe that there could be a world one day without masters or peasants, but it came to pass. Similarly, many of us may find it hard to believe today that there could be a world without marriage or the concept of children as the property of their parents until a certain age, or that people have a duty to sacrifice their lives for a nation's aspirations, but there is an equal likelihood that these things too will come to pass.

I guess the real question is if we will end up like the woolly mammoths, buried in the tundra to be excavated years hence by some other species that made the transformation to the new paradigm more successfully than us, or we will somehow transform ourselves to the new rules and realities... Time will tell.

But get ready. The first winds of the new paradigm are already whipping up the leaves around us. There will be rain after that and thunder and lightning. It will be a real storm, one like we have never experienced before. It won't work to close all the shutters and wait for the storm to pass, because this is a transformation, not a period of chaos after which everything will return to what it was before. This is the identity paradigm, and it is the invitation to define anew who we are.

Imagine there's no heaven

It's easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us, only sky

Imagine all the people

Livin' for today

Ah

Imagine there's no countries

It isn't hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion, too

-John Lennon

Imagine…

Source

Download the full What the Future:

Download the full What the Future: